On the difference between the 60s we see in Last Night In Soho and the actual (conservative) costumes of the eras.

We’re going to hang up my love for the 70s for just a moment to chat about the equally fascinating 60s. Frankly, ever since I saw Last Night in Soho its aesthetic has been stuck in my head. That whole film is a delight for the eyeballs of hedonists, but the fashion in particular (and the fact that the premise is all birthed from the life of a fashion student) gives us so much to explore.

Soho Style

If you haven’t stepped inside a movie theater in months (no shame!) here’s the gist – Fashion student Eloise moves from the countryside to the big city of London to attend ~fashion~ school. Feeling alienated from her classmates, she opts to live off campus and rents a room that subsequently gives her vivid dreams of a hopeful singer named Sandy trying to make it big in 60s London.

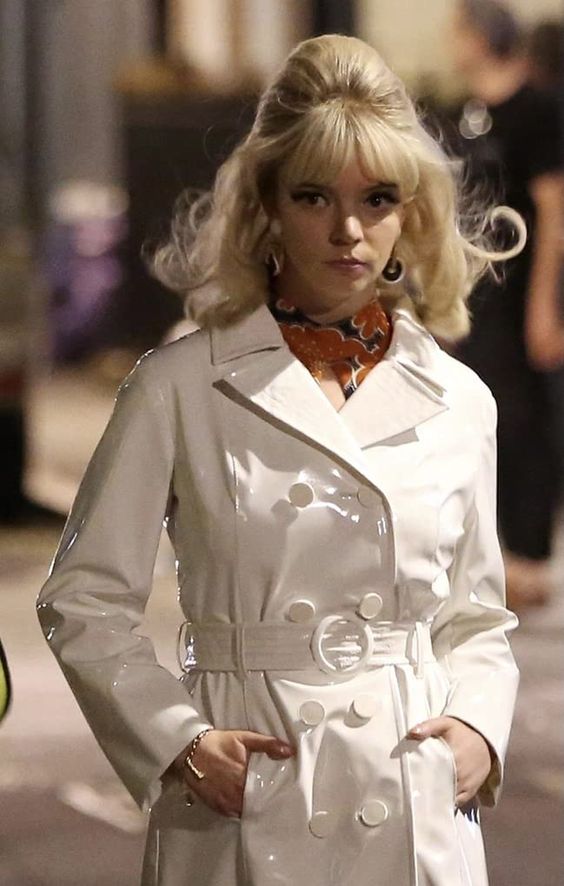

The 60s, Soho, and vivid dreams gave a vast playground for costume designer Odile Dicks-Mireaux to create in. That freedom gives the film this wonderful feeling where you feel just as spellbound as Eloise is by the decade. I too want to dye my hair blonde and buy a knee-length, white raincoat after seeing Sandy flounce around the streets of Soho looking absolutely fabulous.

Funnily enough, Sandy’s costumes were in part inspired by other films’ design of the time. The striking white mack comes from Darling (worn by Julie Christie as an opportunistic model.) A master list of films from the decade, documentaries, and 70s horror curated by director Edgar Wright were the jumping off point for the creative team. So, while period accuracy was certainly a factor, the effect on screen was just as much of an influence.

For example, Sandy’s first look, the peachy, swing mini, suits the mod shape of the decade’s dresses but Dicks-Mireaux added more layers and levity to the fabric to make her dancing on the floor of the Cafe du Paris more commanding, elevating the simplistic shift typically seen at the time.

False History (sort of)

The source of inspiration is interesting given that costume design of the time was still pretty removed from the trends we associate with the 60s. Color blocking, iconic boots, punk leather, and the roots of the hippie way of life were confined to youth culture and protest footage rather than influencing Hollywood.

Some of the most iconic actresses were still dressed according to the same principals of the 50s. As Nancy J Hajeski puts it in Hollywood Fashion, the industry remained conservative and held onto the glamour of the previous decade rather than contending with the new wave of trends and sentiments of the youth. The likes of Doris Day, Audrey Hepburn, and Julie Andrews were twirling away in their full skirts and high collars well into the decade.

There are, of course, a few exceptions. Jane Fonda gave us the cute about-town looks in Barefoot in the Park, and the iconic futuristic meets mod bodysuits in Barbarella. Nancy Kwan, though typecast as ‘exotic’ promiscuous women, wore great examples of the decade’s sexy silhouettes and burgeoning interest in eastern trends. And Goldie Hawn swooped in at the close of the decade making sure miniskirts, boho separates, and hippie fashion made it to the big screen.

Chess, Spies & Trends

But when designers look back on the 60s now, the focus is on the subcultures and runways and the trends they created. The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and The Queen’s Gambit sit firmly within the fashionable set of the era. Queen’s Gambit specifically had an eye on the latests trends since costume designer Gabriele Binder had the gift of a character who loves fashion and a well developed journey for them to move through.

While Queen’s Gambit is masterclass in fashion history from saddle shoes to Beth’s final black and white ensemble, Joanna Johnston through the chronological rulebook out the window for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. She went off feeling rather than history, pulling from all sorts of trends throughout the decade, even if in the plot those years hadn’t even happened yet.

The result is a an extra bold take on mod style. Especially for mechanic turned spy Gaby, it’s all about those bold colors in orange and green and patterns of ’67 and ’68. Everything was meant to look expensive and luxurious; the epitome of a guilty pleasure spy film.

Even without the color, our campy villain Victoria is decked out in sharp geometric pieces, leather waistcoats, and a ring for each finger. It’s a costume-like approach to dressing the 60s, but one that Johnston keeps just on the right side without falling into an abyss of tackiness.

Who’s Right?

It’s a funny thing how inherently a costume designer is rewriting history in the way they decide to approach historical dress. From the minor adjustments for modern ease to the “I totally did not pay attention in history class,” I think they all have their place in different genres, don’t they?